Koch Brothers-- Looking For The Roots Of The Problem

-Posted on Down With Tyranny! on November 13, 2011-

The new issue of the Texas Observer digs around in the fetid sewer that is the Koch family background. Yasha Levine's sleuthing helps put in perspective exactly why the Koch's have made themselves the biggest threat to American democracy since Adolph Hitler-- and for many similar-- if not identical-- reasons. To understand why Charles and David Koch are using their billions to assault American democracy-- even teaming up with Iran (the way their father had teamed up with Stalin) to do so-- you have to look back at the history of this demented, hate-filled family. There Levine finds the roots to their antipathy towards democracy, equality, public education, Social Security, organized labor, environmental, consumer and financial protections and the 99%. They've spent hundreds of millions already and plan to spend another $200 million in 2012 electing 1%-ers like Paul Ryan, Mitt Romney, John Boehner, Mitch McConnell, Scott Brown and other right-wing anti-government sociopaths hellbent on turning back the clock on America. Levine starts with their grandfather a wealthy Dutch-German immigrant who settled in Texas and brought his foreign, hate-filled fascist ideology to his new country, where he tried enforcing it on the people he found here.

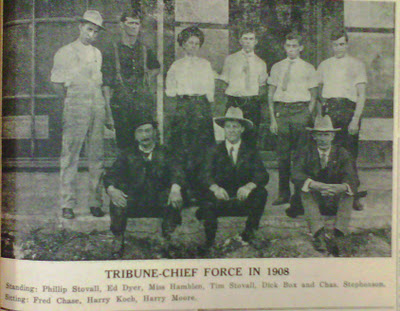

Little has been written about Harry Koch. He's the least-known member of the Koch family, which has been marching under the same laissez-faire banner for the past three generations. Harry Koch emigrated to America in 1888, settled in a North Texas railroad town and became a newspaper publisher and aggressive corporate booster. He advocated for railroad and banking interests, amassing wealth and helping big business fight organized labor and squelch reforms.

Much of the Koch brothers' ideology can be found in Harry Koch's newspaper editorials of nearly a century ago. Take, for instance, the Kochs' current fight against Social Security. Harry Koch took part in a multi-year right-wing propaganda campaign to shoot down New Deal programs. Grandfather and grandsons employ eerily familiar talking points to bash government pension and welfare programs.

"No political system can possibly guarantee either a national economic security or an individual standard of living. Government can guarantee no man a job or a livelihood," Harry Koch wrote on February 1, 1935, nine months before Charles Koch was born.

Fast-forward 75 years and you can see Charles Koch using the same lines of attack in his company's newsletter: "government actions ... stifle economic growth and job creation, which in turn will significantly reduce the standard of living of American families."

...Harry Koch's rise from immigrant small-town newspaper publisher to entrenched business heavyweight might seem like a classic coming-to-America story, confirming that through hard work, perseverance and luck, anything is possible. But that narrative would be misleading. Harry may have lived among settlers who struggled to eke out a living on the frontier, but he was never really one himself. The difference was right there on the surface for everyone to see: While Harry Koch prospered, almost everyone else in North Texas descended into poverty.

On top of the crippling boom-and-bust cycles that gripped the country from the 1890s through the late 1920s, settlers faced crop failures, low agricultural prices and real estate booms that made it impossible for new farmers to afford land. Many sunk into deep debt and poverty.

The misery and hopelessness of frontier life sparked a powerful new grassroots populist movement, which sought to reform and curb the worst of corporate abuses. Harry Koch was not sympathetic to the cause. (In 1897, while the country was still in the grips of one of the worst economic depressions in its history, Harry Koch penned a long, gushing account of a luxurious trip to a convention thrown for boosters and businessmen in Galveston. Between detailed descriptions of all the oysters eaten and champagne bottles emptied at swanky parties, Harry expressed shock and outrage that the street railway union organized a strike during the convention and forced attendees to temporarily move about on foot. But not for long. "Santa Fe officials took pity on the suffering newspaper men and made up a train to Woolman's lake where the oyster roast was to be held," Koch wrote approvingly.)

In a series of early editorials, Harry Koch scoffed at the idea that land rents should be regulated, and ridiculed the plight of heavily indebted farmers, writing that while they might find indebtedness unpleasant, a much bigger problem was their laziness and inability to take care of the farm equipment they had purchased on credit. He patronized Quanah farmers with platitudes about honesty and success: "Be honest. Dishonesty seldom makes one rich, and when it does riches are a curse. There is no such thing as dishonest success." He delighted in the fact that unlike other cities and towns across America-- filled with strikes, riots, political agitation and violent unrest-- the people of Quanah largely steered clear of politics, concerning themselves with what they understood best: hard, honest labor. "A very commendable trait among western people," Harry wrote, "is that they have no time to give to politics."

Throughout the 1890s, Harry never shied from using his newspaper to promote specific business interests and as a platform to express his aristocratic views on society.

But something began to change at the turn of the century. Koch shed his abrasive attitude toward the masses and began reinventing himself as a champion of the common man.

In 1901, Koch published a long editorial that hinted at this transformation. In the piece, he defends popularly embattled trusts and monopolies with the counterintuitive argument that such protectors of wealth were a force for the common good. He based his argument on the false notion that trusts lowered the price of consumer goods:

"Let this thing be borne in mind as significant, that all real trusts, all that are destined to succeed and endure, are established on a basis of permanent lower prices for their products. Everybody knows that sugar and oil have been considerably cheaper since these industries have been under trust control. And the same is true, barring periods of fluctuation, of all industries under effective monopoly, from steel rails to cigarettes."

Harry Koch's transformation was remarkable: Not only was he attempting to convince readers of his point of view by appealing to their own best interests, but he was fleshing out economic arguments in language that his grandsons continue to use today. Harry's defense of trusts reads exactly like the pro-monopoly propaganda regularly cranked out by scholars at The Cato Institute-- a libertarian think tank founded by Harry's grandson Charles Koch in 1977. University of California-Irvine Professor Richard McKenzie recently published an article in Cato's Regulation magazine titled In Defense of Monopoly, in which he echoes Harry's 110-year-old editorial, including this claim: "The monopolist does not charge higher prices; it lowers them."

This new rhetorical approach was not Harry Koch's invention. Rather, Harry was being swept up in a larger national revolution in the way American business elites communicated with the public.

At the turn of the 20th century, growing public outrage at the way financial elites were handling the economy, combined with a rapid expansion of voting enfranchisement that increased participation in the democratic process from 15 percent of the population in 1890 to 50 percent in 1920, began posing a real threat to the entrenched interests of American corporations.

To protect itself, corporate America began experimenting with modern public relations techniques and developing strategies to manipulate and manage public perceptions.

Harry Koch was right in the thick of it.